The drive back on Sunday unfolded without incident — at least until we got close to home.

We hit the city right on time, but something was amiss. The Parkway, a six-lane highway running north-south through the east end, held just a fraction of the traffic it should have, even for a lazy Sunday afternoon. Vehicles were present, though (we were dealing with four to five car lengths rather than the usual one or less), so I couldn’t have slipped inadvertently onto a closed thoroughfare. And then, up ahead, I saw one of those electronic billboards placed above the road every few miles or so. It read: Southbound Parkway exits closed for repairs from Eglinton Avenue to Richmond Street, Sunday 6:00 a.m. till Monday 4:00 a.m.

“Son of a fuckin’ bitch,” I mumbled, wondering just how many warnings I’d missed.

“Pardon me?” Rachel said, sitting up and removing her headphones. This was maybe her tenth statement the entire trip.

“Nothing, Hon,” I answered. “Just a slight detour.”

Within minutes we’d passed our blocked exit. The skyline now loomed to our right. A handful of stop-and-go street routes remained as options for the drive home, but my gas-pedal foot remained highway-heavy, so I decided on the one alternate east-side route that, being neither highway nor city street, posted the highest speed limit and held the least likelihood of delays.

I looped around at the end of the Parkway and started back up the Bayview Extension. By this time Rachel had turned off the DVD player, Eric had roused himself from his fully comatose state, and both looked out their windows as we backtracked northward. They’d never been so far south on this road before, one I’d used almost exclusively for avoiding rush hour on downtown job sites in the past, and its inner-city unkemptness, I guess you’d call it, had caught their attention.

“What’s happening?” Eric asked, just now processing information fully after his long nap.

“Nothing,” I repeated. “We’re taking the scenic route for the last leg of the trip.”

“Cool.”

The backsides of graffiti-smeared warehouses lined the incline to our left, their ranks pocked with the odd razed and rubble-littered lot advertising the virtues of its future townhomes or condos. But not one of the virtues posted could be classified as a view. To our right, multiple commuter tracks, busy with switches and lights, hugged the weed-covered banks of the river running north through the city. The river itself sat brown and low from the hot summer, and on its far bank, the ghost parkway we’d just left weaved into the distance like its paved Siamese twin.

We approached the Extension’s first set of lights amid thicker traffic than I’d expected, an obvious side effect of the dysfunctional highway, and as it turned amber, then red, we coasted to a stop ten cars back from the intersection. A second later, a young, heavily bearded panhandler bounded from his seat by the curb and approached the first car in our lane.

He stepped from car to car, waving a crusted Blue Jay’s cap in his right hand, begging and sporting a grimace that totally distorted what little you could see of his dirty, furry face. With each rejection, he stamped a grimy sneaker on the asphalt like a child rebuffed and moved down the line.

“C’mon c’mon c’mon,” I said, eyeing the approaching menace and the traffic lights simultaneously.

“Who the heck is that?” Rachel asked, sounding more intrigued than scared.

“That,” I responded, “is Crybaby.”

The lights turned green just before he reached us, and as we began to move he leered through the front passenger window.

“Please, buddy, please! Could ya spare some change?” His pleadings washed over us in a Doppler-effect warble as we sped away.

I peered into the rear-view mirror and saw the back of the kids’ heads; they’d turned to drink in Crybaby’s forlorn gaze as, with his shoulders hunched and his fists firmly planted on his hips, he unleashed his opinion of us.

“Crybaby?” Rachel repeated, smiling broadly; almost instantly the smile turned into giggles.

“Good one, Dad,” Eric said, joining her.

I kept driving and the kids kept snickering. Occasionally, I’d hear one of them repeat “Crybaby,” and follow it with a snort. In the approximate mile between intersections they didn’t stop, and with the heavier flow of traffic, we’d locked into the Extension’s red-light pattern.

“There’s another one,” I said, as we pulled up to our next stop. “These guys are here every weekday, but I didn’t think they worked weekends.” I paused and reflected before saying, “They must have come out because of the exit closures.”

The kids were quiet for a second, then Eric burst into full-fledged laughter and sputtered, “Work! Stop it, Dad. You’re killing me.”

Rachel, though, kept her composure, asking, “What’s this guy’s name?”

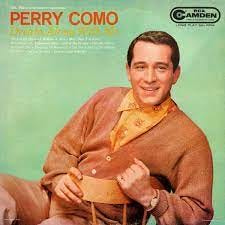

Any references to the pre-millennium past were hit and miss with the kids, and I suppose some serendipity came into play when I slipped them this guy’s moniker, because their understanding of my forthcoming answer once more existed due to TV’s most cherished gift: useless information. A few months earlier, pre-blowup, all of us had been sitting around watching an A&E bio on Perry Como, and a number of issues had arisen upon its viewing, the foremost being how nerdy he’d seemed to Rachel and Eric (music included), especially with his well-trimmed, side-parted hair and accompanying cardigan —what I’d dubbed a “Perry Como sweater” at the time.

The man making his way down the line of cars ahead of us had always, on some weird level, reminded me of Perry. Unlike the others along this corridor, he was clean-shaven, and he wore a cardigan that, although ragged and filthy, seemed to fit his laid-back demeanor. He kept his thinning hair short and Brylcreemed, and he liked to drag a comb through it as he stepped from car to car with his free hand thrust out, palm up.

I’d wondered about his strange ritual on previous drive-bys, and the closest I could come to rationalizing it was that this was how he might have spent his last months in functional society years ago, standing outside of office doors, grooming himself, preparing himself for yet another job-interview rejection on his slow, torturous descent into a modern-day version of mythological hell: standing in an urban wasteland with his hand thrust out in perpetuity as an endless stream of cars flew by, belching noxious fumes and extreme prejudice into his face.

He approached us now, mumbling, raking out those few strands of longer hair draped over his shiny, balding pate; each car before us had either ignored him or delivered an emphatic brush off. And as the light turned green and traffic started to roll, I looked back to the kids and said, “Him I call Perry Combover.”

Their explosion startled me, and as we drove past Perry, I saw him looking into our vehicle, staring (with eyes far less glassy than I might have imagined) at the doubled-up, red-faced children laughing at his desolation.

The kids laughed until their eyes grew glassy, and, oddly enough, I found myself in almost the same state, but not from the humor of the situation. At least, that’s how I recall the epiphany striking me as I replayed that existence-altering statement of Eric’s from back in that other lifetime, the one that Maddy had understood so well: We make fun of the less fortunate, too; they’re khaki.

We reached our exit, taking the turnoff just before the intersection. There, two men worked the lights, watching each other warily from their separate sides of the road as they made their rounds. And when Rachel asked what their names were, I didn’t say anything. For the moment I sat rooted in contemplation, taking stock of my position. I’d never meant for this to happen, for all of us to become so thoughtless — no, more than that. So nasty.

But what, exactly, had I done? Was I merely making my way through a life that consisted entirely of rubbing elbows with the hoi polloi (the same life everyone had to live to one degree or another) and preparing my children for the same with some good old-fashioned hide-thickening, or had I transformed them into what I’d dreaded most, into what I suddenly realized I’d been for a long time now (with a capital A), a couple of raging—?

“So what do you call those guys, Dad?” Eric repeated, pulling me from my rumination. “The Glimmer Twins? Butch and Sundance?”

And still I held my tongue. In the past I’d called them the Battling Bickersons, for those occasional times I’d seen them standing on the median, jawing at each other over turf, choice of cologne, or whatever; but now, as the kids urged me on, seeming to revel in the winos’ collective misery, I saw past the nicknames and through the caricatures for the first time.

“You know what?” I said at last. “I don’t have names for them anymore. But by the time both of you are old enough to get your licenses, and with a few more bad bounces, either of you could drive by this same spot and call them Dad or Uncle John.”

* * *

“So, how was the trip?” Maddy asked. “I mean really, now that the kids aren’t around and you don’t feel obliged to sugarcoat.”

We lay in bed, talking in our lights-out timbre; she hadn’t found the opportunity to speak that candidly earlier, when we’d first stepped through the front door, or later still, when we’d gathered around the kitchen table, or I might have been frank. I might have said, “Y’know, I’m not the person I thought I was, and more than that, above and beyond their soft-as-cheese teeth and their possible future battles with … heftiness, let’s say, or substance adoration, I’ve also passed some whopping non-genetic flaws on to the children.”

But now, more than just the hours had dulled the sting of the weekend’s revelations. We lay with a single sheet pushed down and pooled around our waists, giving each other feather-duster tickles, and I struggled to fight off sleep as we talked. For right or wrong, at that moment the world seemed a far better place than it had earlier in the day — back when the kids and I had taunted the homeless, the hopeless, and the mentally ill, that is.

“The trip was okay,” I said at last. Of course, Rachel and Eric had already regaled Maddy with events over dinner, dwelling on cool cousin Chloe, the Ex’s midway, the awesome beauty of Patterson ‘s Creek, and inquiring about just how old you had to be before you could get a tattoo without parental permission. But they didn’t bring up the dialogue the three of us had shared between the time we’d left the Bayview Extension and the time we’d pulled into the driveway. We’d left that amongst ourselves.

“No, it was more than okay,” I amended, as I reconsidered that last small but muscular leg of the journey. “It was good. Eric, Rachel, and I spent some time together, had some fun, and straightened out a few things together. That doesn’t happen all the time.”

“That is good,” Maddy said, and she didn’t press. We continued tickling for a while, then she said, “Oh, by the way. Wendell Berkshire was over looking for you on the weekend. He’s read the screenplay and wants to talk to you.”

“What did you tell him?”

“I told him you’d be around tomorrow. Is that all right?”

“Well, I do have a lot of little things left to finish on the third floor — and that doesn’t even count building the staircase. Then there’s Rose; I haven’t seen her in a while and I’m way behind on my Bible studies. And . . .”

Behind on my Bible studies. No doubt about it, I was home, and that meant embracing all of the oddities my new life supplied. But for someone with no real direction and no concrete agenda, I felt swamped, like my minimal list was endless, its goals unachievable.

“And . . .?” Maddy said, urging me on.

“And what the hell,” I said, feeling myself slide into slumber. “I suppose I can squeeze him into tomorrow’s madcap schedule.”

Thank you for reading. There are only three chapters left in these adventures of Jim Kearns. The new year will bring more short stories, our award-winning screenplays and the new novel.

Have a very Merry Christmas, happy holidays and lots of hope for a great 2024.